What is the relationship between politics and Christian theology, is there any? Understandably, many Christians want to simply shy away, and have nothing to do with the political order in the world. But the fact of being human entails that we are “political animals,” that we are necessarily social beings, and as such, we cannot escape the reality of being  political in some way. Indeed, the kerygma, the Gospel reality Hisself, which of course is God become flesh in the vicarious humanity of Jesus Christ, is the greatest political act of all time. This was not absent from the early Christian experience, indeed, as it was just burgeoning, wrestling over the implications of just who Jesus was had staggering political implications (one way or the other) for the subsequent trajectory of the Church’s reality, vis-à-vis the state, in the following centuries right into the present. Many Christians don’t recognize just how deeply entrenched they are as an “ecclesiopolitical” people, and thus, as a consequence, they shirk back at their responsibilities of being responsible “political animals,” and ambassadors for Christ, in intentional and intelligent ways.

political in some way. Indeed, the kerygma, the Gospel reality Hisself, which of course is God become flesh in the vicarious humanity of Jesus Christ, is the greatest political act of all time. This was not absent from the early Christian experience, indeed, as it was just burgeoning, wrestling over the implications of just who Jesus was had staggering political implications (one way or the other) for the subsequent trajectory of the Church’s reality, vis-à-vis the state, in the following centuries right into the present. Many Christians don’t recognize just how deeply entrenched they are as an “ecclesiopolitical” people, and thus, as a consequence, they shirk back at their responsibilities of being responsible “political animals,” and ambassadors for Christ, in intentional and intelligent ways.

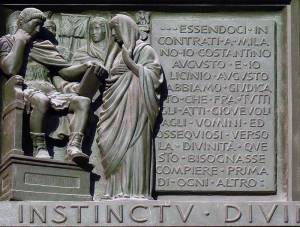

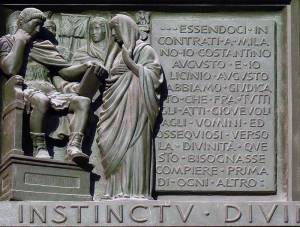

Andrew Willard Jones offers a really nice taxonomy of how the various Christological theories of the early Church, as those developed in the midst of a Constantinian Roman empire, implicated the political theory and actions of the state. These same realities continue to implicate our political climate today. The difference, of course, is that we live in such a secularized state of mind, that it becomes difficult to parse these things out, unless one has eyes to see and ears to hear. The following comes just on the heels of Jones’ sharing the text of the Chalcedonian creed (circa 451 ad).

Here, finally, was a definitive statement on who Christ was, on what really happened at the Incarnation. It had taken over four hundred and fifty years and the concerted efforts of Christianity’s greatest minds to come to this definition. That is how difficult the problem was. The problem was not merely speculative, however. As we have seen, it bore directly on the social order of the now-Christian empire. The conversion of the empire away from paganism in both doctrine and “political” form was a part of the process of coming to understand the fully meaning of the Incarnation. The rejection of Arianism was the rejection of the superiority of the temporal and material. The rejection of Nestorianism was the rejection of the idea that the temporal and spiritual were entirely separate, operating in independent realms. The rejection of Monophysitism was the refusal of the possibility of the spiritual entirely absorbing the temporal into itself. Sorting out Trinitarian and Incarnational orthodoxy was, at the same time, the sorting out of the relationship between what would eventually become known as the temporal and spiritual powers, the powers of the laity and of the priesthood, within a united Church that was a polity. Political theology was integral to fundamental dogmatic theology.[1]

Without getting into the nitty of the Christological theories, which Jones has done prior, what this passage should alert the reader to is just how integral Christology and a Theology Proper were to the development of the Latin and Greek political states. These are the same bases upon which our state is built, indeed the entirety of the Western world. It’s just that we have immanentized the eternal Logos ensarkos (the eternal Word enfleshed) into our own humanity. Following the antique taxonomy, as Jones has laid it out, the state now has fallen prey, once again, to the Arian heresy, wherein the leaders become the gap-fillers between heaven and earth. No longer is the Son of Man elevated as the King of kings, but the Son of “they” has displaced Him with Arian and Bab-elic vigor, elevating their state-being as the Being of all being, as the Godhumanity for all humanity. It is important that we begin to retexture our thinking in these “Christian” ways, such that we come to have a ‘social imaginary,’ once again, that allows us to see things in light of the God’s Light for the world in Jesus Christ. We need to ‘reenchant’ the world, such that we see God of God in Christ as Lord, and ourselves as His emissaries in the midst of a broken state that attempts to see itself as God’s highest creature; to the point that they are the bridge between God and humanity.

What does it mean to be a responsible and intelligent political animal in the 21st century coram Deo (before God)? It means to understand where we are situated in the Kingdom of God, in the heavenly places, and recognize that we stand as ambassadors for Christ, as witnesses, as prophets, through the proclamation of the Good News of the Gospel of Jesus Christ; that Jesus is Lord of lords, and the lords aren’t. Even so, with this realization, we understand that ultimately our witness will end up as the ancient witness of the first Christians, as a witness of the martyrs’ blood. Many of us may never experience a martyr’s death for the sake of Christ, but we can live in such a way, in the state, that under different political circumstances (from now) would warrant such a witness sealed in the shedding of our own blood in echo of our King’s shedding for us. But the matter is a matter of living, and how we do that in this world.

The political state, as Jones helpfully signals for us, is a state rooted in the implications of the Incarnation of God, in a Theology Proper that implicates theories of power and authority. Christians need to learn to recognize this, and think in these terms. This will allow them to better understand their place vis-à-vis the “secular” state. It will allow them to see that ultimately there really is nothing secular at all, and that we are here to bear witness to that ultimate fact of life.

[1] Andrew Willard Jones, The Two Cities: A History of Christian Politics (Steubenville, Ohio: Emmaus Road Publishing, 2021), 79-80.