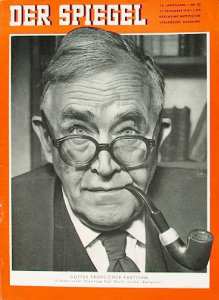

Barth is often depicted as a liberal or “neoorthodox” theologian who repudiates the inerrancy of Holy Scripture, which alone anathematizes him for the evangelical. Barth is often presented as an enemy to conservative orthodox Christianity, with his neo-Kantian, reified Hegelianism ripping to shreds any hope of giving the evangelical churches anything  wholesome and genuinely biblical to cogitate upon. Barth, in many sectors of the evangelical and Reformed churches, is considered as enemy of the state to the health and well-being of historically orthodox Christianity. Barth is often demonized, caricaturized, and flambéed just at the point that someone moves their lips into position to pronounce his name.

wholesome and genuinely biblical to cogitate upon. Barth, in many sectors of the evangelical and Reformed churches, is considered as enemy of the state to the health and well-being of historically orthodox Christianity. Barth is often demonized, caricaturized, and flambéed just at the point that someone moves their lips into position to pronounce his name.

But what I want people to understand is that Barth is none of these negatives I just noted. When you actually spend time with him and his theology the reader will quickly realize that the fears I’ve been listing are unwarranted and have almost no teeth to them whatsoever; save Barth’s repudiation of inerrancy (which his reasons for repudiating this “doctrine” isn’t the same reason the “Liberals” do, but instead based upon his theory of revelation, which I would argue is more attuned and evangelical than inerrancy as a doctrine allows for in regard to a doctrine of Holy Scripture). In line with this desire to show that Barth isn’t the anti-Christ that so many fear, I wanted to share a snippet from him on the way he thinks about Scripture, and how what he calls saga actually fits better with the evangelical desire to see Christ magnified and prime over all our considerations as thoughtful Christians. I want people to come to the realization that Barth offers a genuinely Protestant way to be Protestant without succumbing to what I consider the trojan horse of Catholicity (big “C”), as that continues to make in-roads into the evangelical theologies being recovered today.

As we pick up with Barth, the context we meet him in is on his theory of time/eternity and God. As I alluded to above, he gets into his thinking on saga (v myth think Bultmann), and how that relates to historical personages and events as deposited in the salvation-history we canvas throughout the pages of the both the Old and New Testaments. I will close with a parting word, after the quote, and leave a link to another post I once wrote on this same topic vis-à-vis Barth. Barth writes:

At this point we recall once more the extraordinary significance of chronology in the Old and New Testaments. The whole of the patriarchal ages in Genesis, the rise of the prophets, the various historical co-ordinates of the place of Jesus Christ at the beginning of the Gospels according to Matthew and Luke are presented with a rare exactitude. In this, use may have been made of antiquated Oriental number-symbolics or number-mysticisms, whereby arithmetical error, whimsies and impossibilities may have crept in. But the wonderful thing to be noted here in the Bible Is not the correctness or incorrectness in content of the temporal figures, but their thoroughgoing importance as time data, which is but underlined by incidental number-mysticism and other liberties. There is not a suggestion that revelation and its attestation might have been localised just as well elsewhere or anywhere in historical space. How important it was for the early Church, too, to be able to date the incarnation of the Word, is shown by the passus sub Pontio Pilato [suffered under Pontius Pilate], already in the oldest forms of confession. Revelation is thus and not otherwise localised. In the event of Jesus Christ, as in the various events in anticipation and recollection, it is as genuinely temporal and therefore as temporally determined and limited as any other real events in this space of ours. It is also—think for a moment of the story of creation—described temporally real, where according to the measurements of modern history this description can only be “saga” or “legend.” The Bible also says the same where it transmits parables in the Old and New Testaments. Myths, on the contrary, i.e., narrative expositions of general spiritual or natural truths, narratives which although savouring perhaps of saga do not claim to be narratives, but are to be understood only when stripped of their narrative character, so that the eternal core is liberated from the temporal shell—myths do no occur in the Bible, although mythical material may often be employed in its language (Church Dogmatics I, 1, 373 f.). The dialogue between God and Satan at the beginning of the book of Job “took place on a day” (1.6) corresponding to the day on which subsequently the earthly misfortune burst upon Job. Also Job’s question of God (10.4): “Hast thou eyes of flesh, or seest thou as man seeth? Are they days as the days of men, or they years as man’s years?”, is in the sense of the text certainly not to be answered with a simple negative. In view of the time concept we must not try to avoid the way of Holy Scripture’s “privileged anthropomorphism” (J. G. Hamann, Schriften, ed. F. Roth, vol. 4, 9). Year, day, hour—these are concepts which cannot possibly be separated from the biblical witness to God’s revelation, which in the exposition of it cannot be treated as trifles, if we are not to turn it into a quite different witness to a quite different revelation.

Having said that, we must, of course, go on to say that the time we mean when we say Jesus Christ is not to be confused with any other time. Just as man’s existence became something new and different altogether, because God’s Son assumed it and took it over into unity with his God-existence, just as by the eternal Word becoming flesh the flesh could not repeat Adam’s sin, so time, by becoming the time of Jesus Christ, although it belonged to our time, the lost time, became a different, a new time.[1]

Let the emboldened section serve as commentary on the un-emboldened section. That section lets us understand, better, what Barth is on about. When he refers to saga, he is referring to a real-life historical event as recorded in the biblical witness, and to real-life historical personages; but he is wanting us to read that from the frame of the ‘new-time’ that Christ is for us. In other words, it is saga precisely at the point that historicism and the form criticism of his day could not actually access the “history” of Holy Scripture precisely because such history is only modulated and refracted as it is seen in the Light of the risen Christ. We see here, in Barth, an emphasis on ‘eschatological-time’ breaking in and throughout the witness and canonical formation of the scriptural witness; through its narration of various events and people in those events as they find teleological (purposeful) concreteness in the flesh and blood reality and event of God’s life for the world gifted to it in Jesus Christ.

Saga was the only category, in this context, he could see working to depict the history-delimiting reality that God’s life serves for the creaturely world as its inner and forward grounded reality. As is typical for Barth, his deployment of saga is a reification of that term from its normal usage in literary theory/studies. Nevertheless, it functions in a similar manner; in the sense that the history of God in Christ for the world appears to the profane eyes as just that: legend or saga. But of course, for Barth, this is only because Christ’s reality has not been received by the eyes of faith, but rather the mind of unbelief. Even so, for Barth, saga certainly operates with the general literary characteristics of its normal usage, yet it is reified insofar as what ironically appears as a normal saga, on the superficial, ends up being a saga of epigrammatic portions; the likes of which only those in union with Christ can come to see as greater than the sagas of fictional story or legend. Yet again, saga, for Barth is embedded in a greater theological web of revelation, election, and covenant that puts him onto such a word to help him explicate what he is really trying to say in contrast to many others of his time; others, who indeed, ended up reading Jesus as myth, based upon other optics such as existential encounter provides for the individual knower—albeit cut off from the concreteness of the Christ event and tethered only by the floating brains of those seeking an encounter unencumbered by the solidity of an accessible history. Barth’s usage and appeal to saga is a subversive exercise shaped by his own location and theological formation. Nonetheless, in my view, it has wonderful trajectory as it supplies the evangelical with a way to view the history recounted in Holy Scripture through the reality of Jesus Christ (a real history pre-determined by God’s supralapsarian election to be for the world rather than against it Jn. 3.16).

Here is a link to another post that I once wrote on this topic: Click Here

[1] Karl Barth, CD I/2 §14, 52. The first long section is Barth’s ‘small print’ and the emboldened section is a regular sized font section.