You go online in the Reformed space, and you get the same old trope on a doctrine of election and reprobation; you essentially get the L (imited Atonement) of the TULIP served up as the ‘hard teaching’ Gospel truth reality about the way God relates to part of humanity in a God-world relation. I am here to set the record straight once and for all! This is simply not how God has related to the world, and this based on the analogy of the incarnation. We aren’t groping around in the darkness for snipes, but as Christians, instead, we have been given God’s Self-revelation in Jesus Christ in the incarnation. This is a sui generis (non-analogous) event that itself stands behind all epistemic efforts, at a primordial level, to know God. In other words, to know God is to be reconciled to God; and to be reconciled to God comes unilaterally from God’s free decision of Grace to become human (Deus incarnandus) for us that we might know Him as He has first known us in the Son (the eternal Logos). That said, if knowledge of God is slavishly tagged to God’s becoming for us in Jesus Christ, then to think God, and thus all corollary doctrines, in abstraction from God’s Self-givenness for us is neither safe nor Christian. Based upon this pre-Dogmatic reality we have capacity to move into a discussion on election/reprobation.

Christian Election and Reprobation

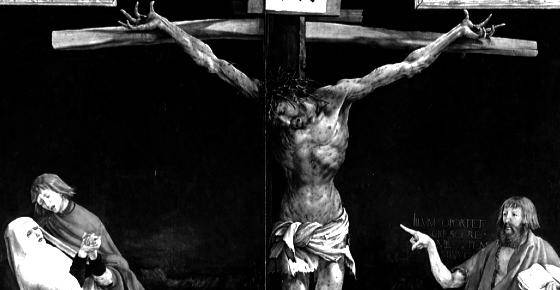

If we are to think election/reprobation from within the Chalcedonian frame of the homoousion of God’s life as both fully Divine and fully human in the singular person of Jesus Christ, and we follow the Apostle Paul’s teaching that ‘He who knew no sin became sin for us that we might become the righteousness of God in Him’ (mirifica commutatio ‘wonderful exchange’), then we will think of reprobation as the general human status, post-lapse, that the eternal Logos assumed (assumptio carnis) in the assumption of our ‘fallen-flesh.’ As such, to think the reprobate status from this concrete revealed status of humanity is to think all of humanity, the only type of humanity present in the incarnation, as reprobate. But the force and anhypostatic ground of the enhypostatic person of the Son of Man, Jesus Christ, was such that its grandiose power, of the resurrection type, its “election and electing” power as it were, could not be resisted by the reprobate humanity that the Christ assumed. In other words, whilst Christ became fallen humanity, in the assumption of our humanity, the total humanity, or the massa, as Christ put ‘death to death’ (cf. Rom 8.3) in His humanity for us (pro nobis), His elect humanity as the ‘Greater, the Second Adam’ was always already going to win the day. That is to say, the everythingness of God’s triune life as active in God incarnate (Deus incarnatus), as the ground of the person, Jesus Christ, has no rival in the nothingness of the fallen humanity that was assumed in the Son’s enfleshment for the world.

This is the implication of the incarnation when applied to a doctrine of election/reprobation. We necessarily think such locus from God’s Self-revelation in Jesus Christ. Instead of wandering around in the wilderness, as if in exile because of disobedience, we flourish under the fount of God’s Self-knowledge as we have been invited into that in the banqueting table of His Holy and Triune Life. Interesting, isn’t it? This is where a discussion like this, on a topic like this, takes us. Typically, when people enter this fray, whether academic or popular, what is almost immediately bypassed is a consideration of how a properly understood Dogmatic taxis, or order, is necessary to acknowledge prior to downstream material discussions on a soteriological doctrine like election/reprobation represents. In other words, people too quickly gloss past the formal considerations that end up, latterly, informing their material theological conclusions when in fact they are ostensibly “theologizing.” When this type of Ramist, or loci styled schemata is uncritically adopted, when the ‘work of God’ comes to be abstracted, and thus separated from the ‘person of God in Jesus Christ’ we can end up thinking something like a doctrine of election/reprobation as if a procrustean bed; we can imagine a theological system wherein Christology can be thought of in abstraction from soteriology, and vice versa. This is how so-called (as I’ve called it) classical Calvinism and Arminianism has arrived at its conclusions in regard to election/reprobation in a God-world relation.

Conclusion

The moral of the story is this: When election/reprobation is thought slavishly from God’s Self-revelation in Jesus Christ, when it is thought of in terms of God’s humanity in the Chalcedonian register, what we end up with is something that is in line with what the biblical categories operate from with reference to election/reprobation (as these categories themselves are intended to map onto the biblical categories of ‘those being saved’ ‘those being destroyed’ see I Cor 1.18). What we end up with is the idea that Jesus Christ is both the electing God and elected human, and that by His free choice to become human, by His free choice to take on our ‘poverty’ we come to have the capacity to participate, ontically, in the riches of His elect humanity status as that is actualized in His resurrection from the dead (cf. II Cor 8.9.

Whatever the consequences of adopting this approach to election/reprobation turns out to be, one thing the exegete can rest assured of is that they are thinking in terms of the ecumenical grammar, the ‘creedal grammar’ of the Church catholic. If this is important to the exegete, then wherever this type of ‘Christo-logic’ might lead, said exegete will repentantly follow. Insofar as Jesus thought that the canon of Holy Scripture referred to Him (cf. Jn 5.39), then it behooves the exegete to imagine that their respective repose in the Chalcedonian grammar, constructively received, will present them with solid footing, no matter where that proverbial climb of theological endeavor might lead them. Further, when following Jesus’ lead, as far as thinking the res or ‘reality’ of Holy Scripture, our relative ascription to this or that ‘party theological tribe’ will end up taking second, if not third and fourth seats. In other words, the ‘catholicism’ of Christ’s life requires that a person is willing to think outside (if that’s what ends up happening) of their pet theological demarcations. That is to say, once a person adopts the hermeneutic proposed by the creedal grammar of something like Chalcedon, however that might be constructively received, it is the adoption into this hermeneutical family that said person will be formed by for the rest of their days. If this leads them, in explicit terms, to abandon say something like their beloved classical Calvinism, then so be it. There is no creed but Christ.