More thoughts on the properties of God for my philosophy of religion class. As I have been responding, this week, surrounding God’s omniscience, freedom, goodness, and necessity. These are my first two responses.

“Could anyone other than you, right here and now, know what it was like to be you, right here and now? Why or why not? What are the implications of your answer for the notion of divine omniscience?” (this, posed by the tutor for the class, based on our readings of T.J. Mawson)

Omniscience. Someone might have the capacity to know what it is like to be me by way of a general set of shared commonalities. So, they might be able to be empathic, in regard, to “how I see things.” But at a basic level, no, someone else, definitionally, cannot know what it is like to be me from the inside/out. I could explain to them what it is like to be me, insofar that I could in fact explain and articulate that; but that would entail the self-limiting factors of my own capacity, as a finite human being, to express such things. Equally, they could “get” what I’m saying to an extent, insofar that they might have similar experiences and socio-cultural conditioning to my own. But that would be as far as we could get.

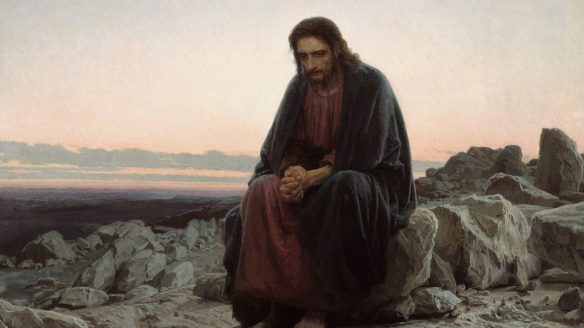

Divine omniscience, on the other hand, has no such boundaries. Indeed, the living God can know exactly what it is like to be me because he knows everything. And to stretch further: from a Christian theistic perspective, he can know me from the inside/out because he assumed my humanity, and yours, and everyone’s in the incarnation. From this God has a shared human connection to our humanity. Or it might be said, that humanity has a shared connection with his humanity for us. Even so, more broadly, the Bible says in the epistle to the Hebrews, “that everything is bare and naked before Him to who we must give account.” On my view, we can only really understand divine omniscience analogously. That is to say, that as we look out at being all knowing “conceptually,” as finite beings, as humans we come to apprehend what that entails by thinking about what that could be like. We can do so as we commiserate with each other in regard to shared experiences, and socio-cultural conditioning. We might be able to extrapolate from there, and imagine a greater instance of that in an amplitude that goes beyond that imagination itself. That said, it isn’t we that predicate God’s properties, but he who predicates ours; indeed, as we are created and re-created in his humanity for us in Jesus Christ. So, by way of order, in order to think what it means for a being to be omniscient, I prefer to not work from a negation (of human being), in order to construct a positive property for God. But instead, my preference is to think God from God, as God first has spoken Himself for us in and through the Logos of God, Jesus Christ. Since in His Self-revelation and witness, particularly as that is attested to in Holy Scripture, God has made clear that He knows everything; even down to the very beings of our hearts and minds. Philosophy might be able to posit categories that seem to correlate with that; indeed, with reference to a pure being. But ultimately, I would argue that those are only accidentally correlated with who God has Self-revealed himself to be. Insofar that God’s Self-witness remains pervasively and personally present in the world through the Christian witness. And thus, such logoi, or knowledge points are present, even to the philosophers, because God’s Self and personal witness is always already ubiquitously present in the world.

“If you were God but had somehow the choice to be either inside time or outside time (temporally everlasting or atemporally eternal), which would you choose and why? Explain your own understanding of the difference between these two possibilities as part of your answer. Must God’s relationship to time be only one of these? Explain why or why not.”

Eternality. If I was God (God forbid it!), and the only alternatives were to be temporally everlasting or atemporally eternal, I would choose the latter; to be, atemporally eternal. Again, from a Christian theistic (meaning trinitarian) perspective, I take God’s being to be beyond being (to borrow a little from Aquinas); which entails, that I believe that God is absolutely Self-determining, without contingence, to be who he is, and always has been, within the environs of his eternally existing and interpenetrating life as Father, Son, and Holy Spirit. Classically, this type of absoluteness, as Mawson underscores and develops, is a feature of God that precludes God’s life from any type of contingently construed conditionality (i.e., dependence on the natural order, or something). Contrariwise, being temporally everlasting, again as Mawson defines it, entails the possibility that God might have some type of potentiality vis-à-vis the world built into his life. This might be an attractive way out for folks who want to reject the classical theistic alternative, like the open theists among us, but for me it is much too high of a price to pay. It is too high of a price to pay because, in my estimation, it makes God contingent upon us; upon our libertarian freewill, so to speak. But then again, what is freedom?

But I think to think in terms of either a temporally everlasting or atemporally eternal God, as if this binary represents the whole continuum, is false. I think it is false primarily because I believe, confess even, that God’s being cannot be constrained by human reasoning, per se. That isn’t to say that I don’t think some of the grammars developed by the philosophers cannot be of assistance when God-thinkers are attempting to give an articulate and intelligible representation of God in human speech. But it is to say that I believe it is possible, and even necessary, to think God’s triune life as time-predicating in itself. I believe God’s triune life is a novum (‘a new thing’ for which there is no analogy). As such, it could be said that God’s life is both atemporally eternal and also temporally everlasting, insofar that the former, in an antecedent way, predicates and tinges the latter. So, in this way, to take the philosophers’ language, it would be to think the triune God in combine, wherein the persons of God’s life, in their unitary being, condition what is given concretization in the temporally created order. Such that to think atemporality and temporality of God’s being in competition one with the other becomes a non-necessity. In this frame, time has value insofar that God’s life of Father in Son, Son in Father by the Holy Spirit creates the inner-space for time to obtain, as that first obtains in God’s triune and eternal life of communion; one with the other. This would give us a time frame that is conditioned by personal relationality, that is both eternal and everlasting; the former predicating the latter. Much of this remains a mystery (since God is ineffable). But this is how I might attempt to think an alternative theory of time based on the analogy of the incarnation of God in Christ.