Pure nature, I’ve referred to it before at the blog. In my view it represents all forms of ill-formed theological efforts in the history of theological efforts. There are attempts in something like the ‘mediating’ theology of the Novuelle Theologiae of someone like Henri de Lubac, wherein the hard edges of a Tridentine (and scholastic Reformed)  development of pure nature are softened, but I believe the whole apparatus must be abandoned in favor of a genuinely Christ conditioned, and thus, Grace actualized notion of a God-world relation. But you might still be wondering what a natura pura (pure nature) entails. In order to get a better grasp, let me share a citation Barth makes in his CD to G. Wünsch’s description of what reduces to the entailments of a ‘pure nature.’

development of pure nature are softened, but I believe the whole apparatus must be abandoned in favor of a genuinely Christ conditioned, and thus, Grace actualized notion of a God-world relation. But you might still be wondering what a natura pura (pure nature) entails. In order to get a better grasp, let me share a citation Barth makes in his CD to G. Wünsch’s description of what reduces to the entailments of a ‘pure nature.’

“1. As everything has the origin of its being in God and no creature can disown the Creator, there is no opposition in kind between natural, i.e., this-worldly, immanent morality as directed by naturalistic and human criteria, and, on the other hand, Christian morality as determined by the being of God. Only the pure being of the world and man, as these are in themselves apart from sin, must in its pure essentiality determine the laws of the moral. This is pure being, which lies at the base of all empirical existence and can be disengaged from it, is the obligating being in the sense of the pure law of nature; it is the means of the primal revelation which is accessible to every man.

2. But Christian morality is directed to the God of the revelatio specialis [special revelation] which has taken place in Jesus Christ. It includes natural morality, which, with the help of an overbracketing of values, will always be an idealistic morality, and in content it shoots out beyond it. Its particularity is given divine sanction to natural morality, to recognise its commands as expressions of God’s will effected by creation, and to demand reverence not only for the essence of the world, but also for the being of God. It demands an attitude on the part of man to God which corresponds to the distinctive relationship to Him; the relationship of creature to Creator, or rather, of pardoned sinner to gracious God, a relationship of absolute reverence, love and gratitude.” (G. Wünsch, Theo. Ethik, 122ff)

In Marburg, where this was written, it was not appreciated that the very same thing could be written in Münster, Paderborn or Freiburg—only better.[1]

Barth, in his parting comment, in regard to Wünsch’s description of things, makes clear that he sees a correlation to what he, in the context of this section of the CD, believes is present between his former ‘neo-Protestantism,’ and the Tridentine Catholic understanding of the relationship between nature and grace. That is, he believes there is a broad commitment to the Thomist axiom of ‘grace not destroying but perfecting nature’ as the basis of so much of the theological developments; whether those be of the classical Romanish type, or the modern Teutonicish type. Barth believes no matter who is giving ‘pure nature’ (as understood in the ‘analogy of being’ analogia entis) a basis in their respective theological treatments, that such theologies ought to be repented of post haste.

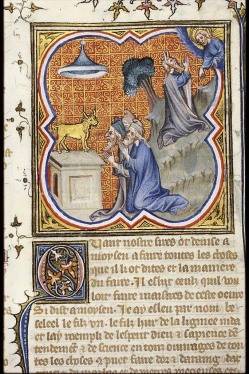

Even today, in my own experience and exposure, natura pura continues to dominate the theological scene; whether that be of the highest academic echelons, or the lowest popular-level domains on YouTube. When nature is thought of as an independent antecedent reality (to God) of its own standing—even if the pious assertion is made that “well, of course, God is still the Creator”—then only idolatry of Pelagian and synergistic and syncretistic force can reign. According to the “Barthian correction” there is nothing anterior to God; God is God. As such, nature has no meaningful independence of its own, which of course Barth’s reformulated doctrine of election makes clear. That is, if the Son eternal, to be incarnate and incarnated, is the enhypostatic ground and grammar of creation’s (nature’s) telos (purpose), then to attempt to think grace as only a perfecting of an already existing, and ostensibly abstract nature, from God’s protological purposes (i.e. the Lamb slain before the foundations of the world) is to give nature a primacy and primordial-ness that, at least from a genuinely Christian taxis (order) of things it cannot have. And that’s what this is all about, isn’t it? Aren’t we as Christians supposed to be forwarding, bearing witness to Christ as the primordial reality of all reality, as Maximus the Confessor understood, bearing witness to the Cosmic Christ? And yet somewhere along the line the gold plundered from the Egyptians, or the Greeks, as the case may be, was manufactured into a golden-shiny thing that has become the way “classical” Christians have ostensibly thought the true and the living God.

Barth et al., including myself, is calling Christian theology back to its apocalyptic and revelational ground in a slavish commitment to a Christ concentration that can only be known through genuinely thinking God from Christ principially. As Christians, if we were to make the proper theological connections, if we were to “connect-the-dots” and implications of theological ideas, if we were to recognize, among some, respectively, that in fact there are theological ideas to connect in the first place, then we would be all the better to live the doxologically oriented life that a genuinely Christian theology, which understands God is God, ought to bring us to. Instead, among all Christian theological demographics (ranging from the academic to the popular) what is being “recovered” for the churches is a theological discourse and development grounded in pure nature. May this become anathema.

[1] Karl Barth, Church Dogmatics II/2 §36 The Doctrine of God: Study Edition (London: T&T Clark, 2009), 25-6.